Tunisian lessons on Lampedusa and ambivalences of an open situation in the Mediterranean

“The goal is for the Mediterranean to be a calmer sea, said the Italian Foreign Affairs Minister Antonio Tajani on the eve of signing the memorandum of understanding between the European Union and the Tunisian regime of Kaïs Saïed. But the Mediterranean, the central part in particular, is by no means “quiet.”

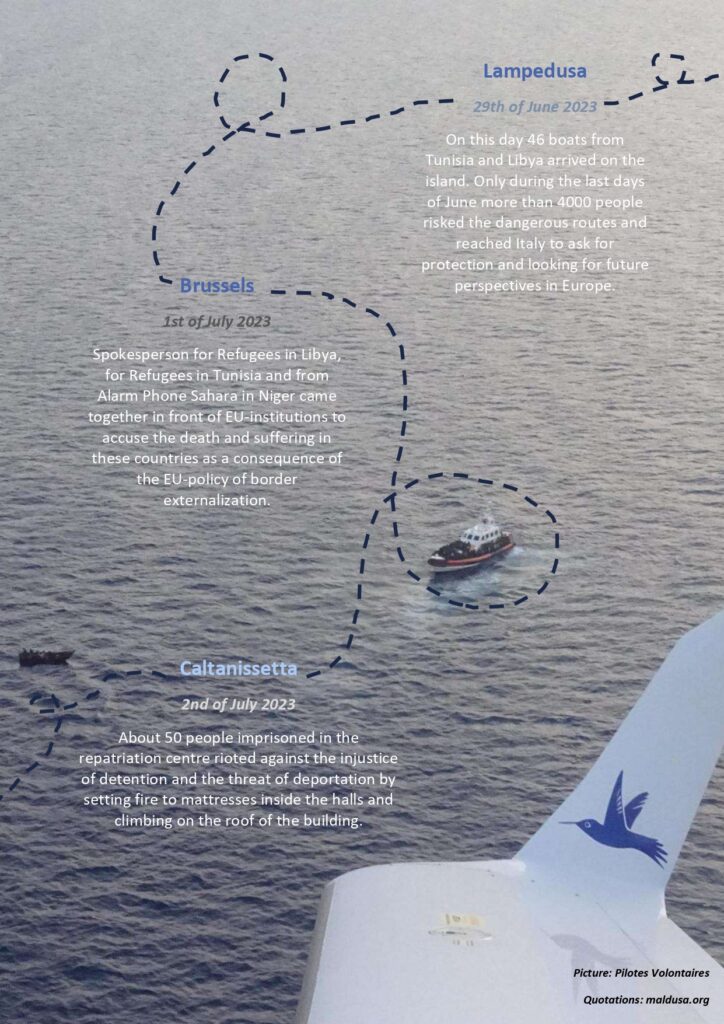

According to data by the Italian Ministry of the Interior as of 14th July 2023, 74.718 people have landed in Italy since the beginning of the year. Of which 3.120 departed from Turkey, 28.825 departed from Libya, and as many as 42.773 from Tunisia. It is on this last route that all the attention of recent months has been focused. Starting with the situation on the Tunisian mainland, identified since last year by people moving from Africa as a possible and viable alternative to Libya, less violent and cheaper. But this place of passage has also become, with the authoritarian turn of the presidential regime in the face of a deep economic and social crisis, the scene of a racist campaign from above and pogroms in the streets. A place to leave as soon as possible by taking to the sea.

Thus, mostly on dangerous iron boats departing from Sfax, the flow to the island of Lampedusa – the “Gateway to Europe” – has become continuous and unstoppable, a precarious route to freedom for thousands of people. Here, the Italian government was forced by migrant pressure to change the management and reception of arrivals: the declaration of a ‘state of emergency for immigration’ and the ‘full powers’ assigned to a prefect-commissioner of Civil Protection meant a sharp change of pace in the management of the hotspot center on the island and of transfers.

With the entry of the Red Cross, the length of stay in the hotspot was drastically reduced, 24/72 hours at most, with an enhanced ferry system of civil and military ships and sometimes planes to transfer people to Sicily and other Italian regions, as documented by Maldusa project. At peak times, migrants are forced to stay longer, in undignified conditions, and their rights to proper information and access to procedures for applying for protection are often not guaranteed. In the same way, the reception system throughout Italy is revealing all its inadequacy: new tensions are erupting, with riots in recent days in the detention centers (CPR) in Caltanissetta and Milan, and new conflicts are opening up between the central Government, Regions and local Administrations.

Speed and efficiency of procedures and transfers show a possible ambivalence: on the one hand they offer spaces of greater freedom to people on the move, on the other hand, in the government’s intentions, they should prepare the ground for more effective detention mechanisms aimed at expulsion from Italy and forced deportation to “so-called safe third countries.” Every single person detained in a CPR and/or deported represents unacceptable violence but, for the moment, the government’s results on this are still scarce: in the last year just over 2.000 people forcibly removed against more than 105.000 arrivals.

Even at sea, the pressure along the Tunisian route has produced significant changes in the tactics adopted by the Italian authorities. Southwest of the island of Lampedusa, the rescue assets deployed by the Coast Guard and the Guardia di Finanza are clearly insufficient and their ships and operatives overwhelmed by the number of people at sea at risk of shipwreck. This is due to the government’s political choice not to take note of the real situation and the consequent refusal to deploy adequately larger and more numerous assets, including those of the Navy.

For some weeks now, this has also led to a change in attitude towards the Civil Fleet: small non-governmental vessels (such as Nadir, Mare*Go, Aurora, Astral, Aita Mari, Rise Above) operating from or around the island are actively involved in rescues and, increasingly, larger vessels (such as Geo Barents, Humanity1, Ocean Viking, Open Arms, Sea-Eye 4), after carrying out an initial rescue in the Libyan SAR area, are diverted to Lampedusa under the direct coordination of IT MRCC Rome for rescue operations on people arriving from Tunisia.

But, even in this aspect, we must consider the ambivalence of the situation: this is by no means a return to the ‘golden age’ of cooperation between authorities and NGOs, but an instrumental use of the Civil Fleet at a difficult time. In fact, mainly due to the political will of the Viminale, the policy of assigning ‘distant ports’ for disembarkation continues. And the policy of unjustified and vindictive detention of ships on the basis of the Piantedosi Decree continues: it is important to note how, out of five cases of ships temporarily detained for 20 days and sanctioned, on no less than three occasions (Louise Michel, Mare*Go and Aurora), authorities have made the decision to disembark people in Lampedusa, refusing ports more than 36 hours away.

Indeed, we must never forget how, in the structural ambivalence of the phase we are experiencing, the outsourcing of border management remains the main and only shared political strategy of the Italian government, the EU member states and the European institutions. A strategy that these institutional actors are continually forced to remodel and re-articulate in the face of migrants’ irreducible will to practice their right to freedom of movement. And we must never forget how many crimes, how many deaths and how much suffering this political strategy continues to produce. The massacre off Pylos and the responsibilities of the Greek state remind us of this (see the reconstruction below). But also, the daily trickle of “little forgotten shipwrecks” along the route from Tunisia and the continuous interceptions, captures and rejections from Libya. Here we must note and strongly denounce how the collaboration of Italy and Malta with General Haftar’s militias is beginning to produce its deadly effects with new captures and deportations from the sea towards Benghazi and the other ports of eastern Libya, in a horrendous market of political and economic bargaining on the skin of people on the move.

But even here, we cannot fail to see ambivalence looming: thanks to the extraordinary struggles of the Refugees in Libya, which began in October 2021 and have not stopped since, with the successive support campaigns that have come with Un-Fair all the way to Geneva, Libya has long ceased to be just a ‘black hole’ of violence and torture. Even for that context, collective action can produce positive results. How can we fail to recognise the coincidence between the latest mobilisation in front of and inside the EU institutions in Brussels and the liberation of many protagonists of the struggles from the infamous Ain Zara camp in Tripoli?

Resistance and the practice of freedom of movement by migrants, continuity and development of the political and operational capacity of the Civil Fleet, constant pressure from a public opinion enriched by multiple social and religious, cultural and political orientations are not only keeping open, but are deepening the contradictions of the border regime, fighting its brutality. Here, too, there is still ambivalence: on 13th July the European Parliament’s resolution speaks, for the first time in years, of a new institutional SAR mission and of collaboration with NGOs, while the ‘Team Europe’ (composed of Von der Leyen, Rutte and Meloni) signs on 16th July with President Saïed a memorandum of understanding trying to replicate in Tunisia the Libyan business model ‘to stop departures’: hundreds of millions of euros to build a cruel mechanism of capture, rejection and detention. But despite the very high price paid in terms of human lives, this inhuman and criminal model has proven not to work.

The Mediterranean is far from “calm.”

Everything and everyone is in motion. And they have no intention of stopping.

16th July 2023,

By Mediterranea Saving Humans

Article published in Echoes#7 – Moving on.