Coordination and documentation platform for people in distress at sea

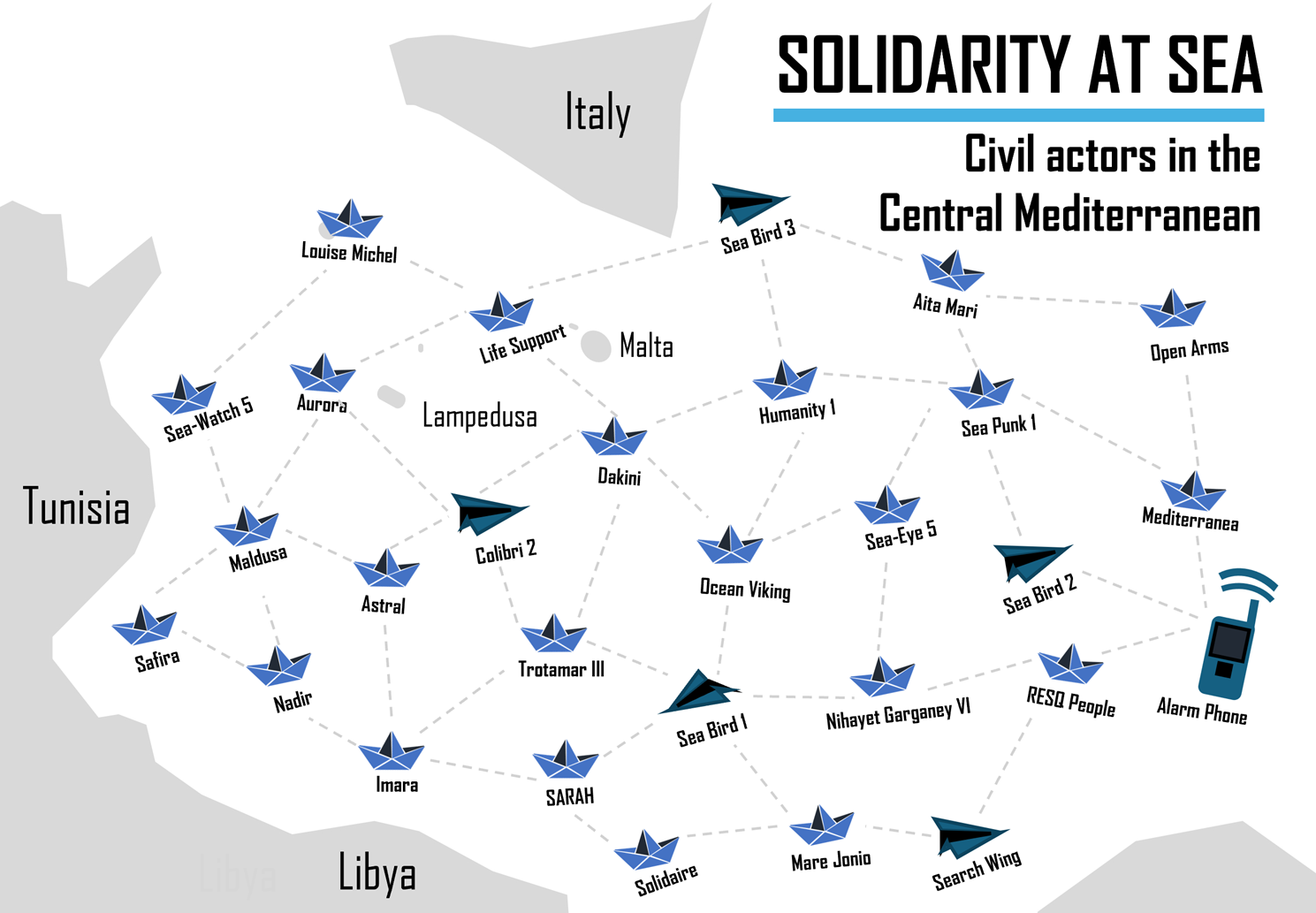

The Civil MRCC aims to contribute towards creating a network of solidarity in support of people on the move. It supports the fleet of NGOs that have assisted and brought to safety tens of thousands of people since 2014. This was done through maritime rescues carried out by NGO ships, aerial monitoring flights with civil aircrafts, as well as through the Alarm Phone hotline.

As a growing network of solidarity gathering different non-governmental actors and individuals with Search and Rescue (SAR) experience in the Mediterranean, the CMRCC:

- Endeavours to hold coastal states accountable for their duty to coordinate search and rescue activities in compliance with human rights principles, and to support ship-masters engaged in sea rescue operations

- Facilitates and improves an effective cooperation and communication between the different non-state actors engaged in SAR operations at sea

- Gathers data and information on cases of distress in the Central Mediterranean area, in order to raise public awareness and support advocacy efforts and research

➜ About us

Echoes from the Central Mediterranean

“Echoes” is a critical review between 20 and 30 pages long, published every two months, addressing actors of solidarity at sea as well as any person interested in border struggles. In Echoes, significant aspects of SAR in the Central Mediterranean are reflected upon, actual topics discussed, analysis and research presented, and the self-organized struggles of refugees and migrants highlighted.

Latest News

-

Biometric experiments and arbitrary practices targeting people on the move

Lampedusa. Picture: Maldusa Over the past month, Lampedusa has become a testing ground for the introduction of new screening and border management tools, most notably the new “Screening Toolbox” package made available by the Frontex Agency. The pilot, which lasted…

-

Reflections around the new European Pact on Migration and Asylum

The new European Pact on Migration and Asylum is scheduled to enter into force on 12 June 2026. The package, adopted by the Parliament and the Council on 14 May 2024, consists of 10 new legislative acts, including 9 regulations…