Reflections on the selective disembarkation strategy in light of the Catania Civil Court decision in the case of the Humanity 1.

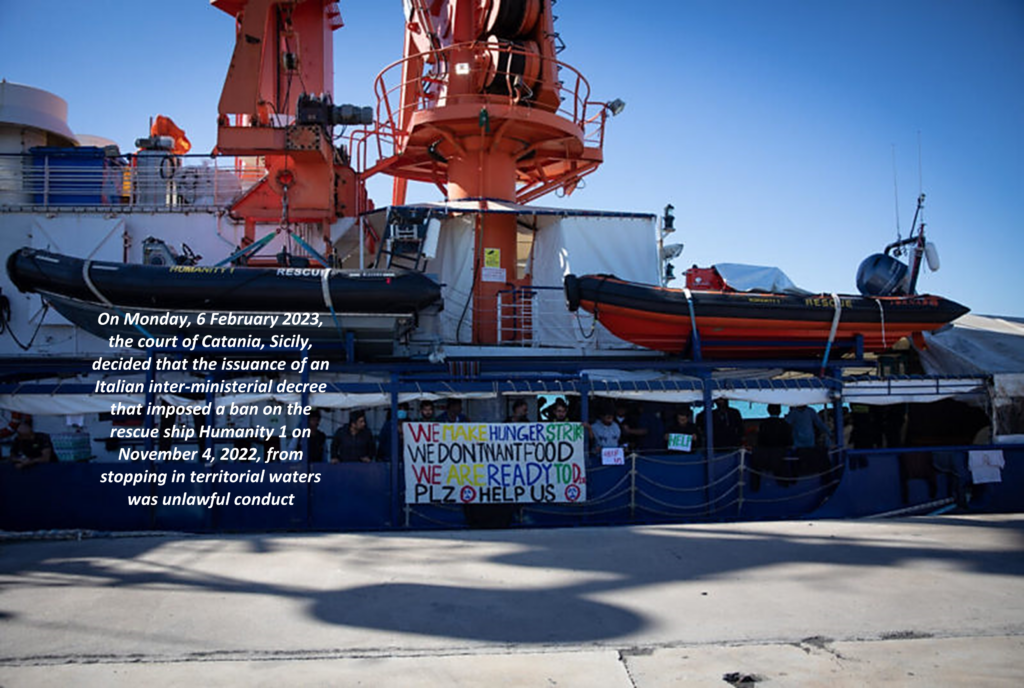

A few weeks after its election, the new far-right Italian government led by Giorgia Meloni started (again) to target civil society organizations involved in search and rescue activities in the central Mediterranean. Between the end of October and the beginning of November 2022, while four NGOs were operative in the central Mediterranean Sea after having rescued around 1,000 persons, the newly elected Italian Ministry of Interior Piantedosi – jointly with the Ministries of Defence and Transportation – started to implement different measures with the aim of preventing the NGOs from disembarking the survivors in Italy. In particular, after reaching out to the Norwegian and German embassies through two verbal notes with the aim of highlighting the flag State’s responsibilities concerning SAR operations carried out in the central Mediterranean, the Italian Government issued two almost identical decrees targeting two of the four NGOs which were at sea at the time, namely SOS Humanity (with vessel Humanity 1) and Doctors without Borders (vessel Geo Barents). These provisions – which were re-named as “illegal decrees” – were appealed in front of the Catania Administrative Court, which finally confirmed their lack of compliance with international maritime law, human rights and asylum law.

The selective disembarkation as a denial of rescue

During the final week of October 2022, after rescuing more than 1,000 people, the ships Humanity 1 (NGO SOS Humanity, 179 survivors), Geo Barents (Doctors without Borders / MSF, 572 survivors), Rise Above (Mission Lifeline, 89 survivors) and Ocean Viking (SOS Mediterranée, 234 survivors) were left in standoff for several days. This was due to the refusal of the Italian government to assign them a Place of Safety (POS), where the rescue operations could have been considered concluded with the disembarkation of all the survivors. These four ships were “managed” differently: while the Rise Above was assigned Reggio Calabria as a POS and the Ocean Viking decided to go to France (despite a statement from the European Commission highlighting the risks to survivors from such a long journey), the Humanity 1 and Geo Barents were targeted with two decrees which stated the following:

“The ships were prohibited from stopping in national territorial waters beyond the time necessary to ensure rescue and assistance operations for people in emergency conditions and in precarious health conditions reported by the competent national authorities.” And “[i]n any case, all the people who remain on the boat will be assured of the necessary assistance for exiting territorial waters.”

From an operational perspective, these provisions were implemented through a “selective disembarkation” strategy, according to which those who were not considered to be vulnerable or sick enough were not allowed to disembark, and potentially subject to a de facto refoulement.

Against this strategy – which was based on an instrumental use of the notions of ‘vulnerability’ and related bio-medical health assessments as a key bordering tool to sustain the differential (de)valuing of human life – survivors, civil society organizations as well as doctors and psychologists put in place several actions of voice and resistance, which finally led to the disembarkation of all the survivors, as a last mandatory step to consider the rescue operations concluded.

The legal action and the Catania Civil Court decision

In parallel, NGO lawyers put forth different legal actions in order to both challenge the legitimacy of the decrees and elucidate their effects on rescued people.

In particular, the people rescued by the vessel Humanity 1 who were considered “not vulnerable” in the first instance, after receiving detailed information regarding their right to access asylum procedures and the rights connected to them, had expressed their willingness to seek protection, without this being followed by any reaction from the competent Italian authorities. On the contrary, they were prevented from disembarking for several days after they had formally and individually expressed their will to seek asylum in Italy.

By law, an asylum seeker is a person who has expressed a willingness to seek protection – without that expression having to follow any particular form – for as long as necessary for the final conclusion of the asylum procedure. Also, under Italian and European law, state authorities are obliged to receive every asylum application, provide reception to applicants and issue them with a residence permit valid for the duration of the procedure. Thus, regarding asylum seekers, states must abide not only by the prohibition of their removal from state territory, but also precise obligations regarding receiving them and ensuring their legal stay.

Due to the persistent refusal of the Italian authorities to disembark the asylum seekers, they approached the Civil Court of Catania to urgently request recognition of their right to leave the rescue ship in order to initiate the asylum procedure. The court ruled several weeks after their disembarkation, which had occurred after the health authority recognized their state of psychological fragility as shipwrecked and from Libya, establishing some important principles.

The Tribunal incidentally declared the illegality of the interministerial decree requiring the captain of the Humanity 1 to leave territorial waters after disembarking the first number of survivors for two sets of reasons, connected to the violation of international law of the sea and asylum law. First, the Tribunal reiterated that the obligation falls on the state to provide assistance to “every shipwrecked person without the possibility of distinguishing, as enshrined in the interministerial decree, applied in the circumstance, on the basis of health conditions,” and that – quoting the Supreme Court in the Rackete case – “a ship at sea providing assistance does not constitute a ‘safe place, except on a mere temporary basis, since it, in addition to being at the mercy of adverse weather events, does not allow for the respect of the fundamental rights of the rescued migrants, among which must be included their right to apply for international protection.” Secondly, the Catania judge pointed out how the asylum rules preclude the prolonged denial of disembarkation since it effectively prevents the exercise of anyone’s right to initiate the asylum procedure.

This preclusive effect on access to the asylum procedure, the Court clarified, violates not only Italian and EU rules on international protection, but also the fundamental rights established by the European Convention on Human Rights, and, in particular, the prohibition of collective expulsions.

This practice would seem to have been immediately abandoned by the Italian government because of its manifest contravention of norms and principles derived from domestic and international law.

Nonetheless, even in light of the government’s attempt to shift jurisdiction over the analysis of asylum claims to the flag states of the rescue ships, this decision appears important because it reaffirms, without ever questioning them, the asylum obligations of the Italian state as the disembarkation country of the rescued people.

By Chiara Denaro and Lucia Gennari, CMRCC legal team

Article published in Echoes#5