So far, this section of Echoes has focused in particular on the Central Mediterranean route, because that is where most of the civilian SAR fleet has operated since 2014.

Without going into detail here on the geographical evolution of civil fleet involvement and deployment, it is possible to observe how the nerve center of search and rescue operations on the part of NGOs has gradually been located on the most dangerous and deadly route: the Central Mediterranean. The initial deployment in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean (due in particular to the conflict in Syria) has been reduced due to the decrease in passages, and at the same time “neutralized” the by criminalization of solidarity and the monopolization of intervention by the Greek and Turkish authorities, who (with the active participation of Frontex) are attempting to lock down a cramped maritime space where the territorial waters of the two countries touch each other without a solution of continuity.

The positioning in the Central Mediterranean of the civil fleet, and its persistence despite years of obstructionism and accusations, threats and criminalization, is increasingly necessary today, not only because of the retreat of the state actors and the pre-eminence of aerial surveillance (mainly carried out by Frontex); but also because of the gradual outsourcing of maritime surveillance to Libya and Tunisia, with the creation of SAR zones of competence which, instead of extending the rescue zones, lock down these areas, further delegitimizing the presence of NGOs and creating the conditions for violations and crimes which have already been extensively documented and denounced.

These evolutions are also reflected in the number of bodies arriving on the Maltese or Italian coasts, which has dropped significantly since 2018, except when shipwrecks take place close to European coasts (Cutro, Pylos, Roccella and many others) and where the authorities cannot evade their obligations and the victims become irrefutable evidence. At the same time the number of shipwrecks or disappearances has increased in international waters and close to the Tunisian and Libyan coasts (as demonstrated by the figures supplied by the Tunisian authorities and the dramatic situation in the Sfax region, with an exponential increase in the number of victims and unidentified bodies occupying morgues and cemeteries).

As repeatedly denounced by the civil society, an increasing number of shipwrecks and disappearances remain “invisible”, and not taken into consideration by international organizations or covered by media outlets, because they take place away from surveillance zones, but also away from zones where NGOs intervene as a priority, or can intervene.

The central-eastern Mediterranean (between the Ionian Sea and Crete) and the central-western Mediterranean (between the Balearic Islands and Sardinia) remain mainly “remote” surveillance zones, but also zones where Salvamento Maritimo, a spanish a public institution responsible for maritime security, were prohibited from conducting monitoring and search operations without receiving distress alerts. This is a consequence of the militarisation of Search and Rescue operations by the Spanish government makes it impossible to account for the number of possible shipwrecks and disappearances.

They can be classified as “minor” routes, but at the same time the number of victims in the Alboran Sea has risen significantly since 2023, and the number of people who left Algeria and disappeared between the Balearic islands and Sardinia remains undetermined. And the Pylos, Roccella and Cutro tragedies occurred along an east-west route. On those routes, most of the requests from families looking for a missing relative remain unanswered. And it is probably on these routes that the involvement of families and loved ones in the search is even more important.

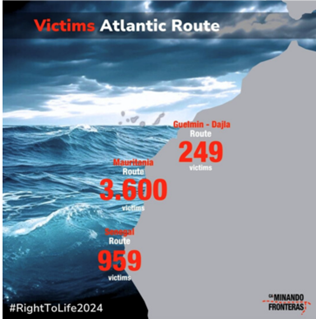

The point here is not to measure the direct impact of control and security logic on the evolution of the different routes, but rather to question the reasons and conditions that make disappearances even less visible, and family searches even more difficult. The Atlantic route to the Canaries, where the gap between the number of victims (according to families and loved ones) and the number of bodies recovered (according to the media and authorities) provides an interesting case study to better understand those challenges.

The Canaries and the Atlantic

According to local organizations, the first case of documented shipwreck in the Canaries dates back to 1999: on July 24, the bodies of nine young people were found on the Playa de la Señora in Fuerteventura (source: Association Entre Mares). The number of cases has increased over the years, in the midst of almost general indifference, despite the mobilization of local civil society actors and the gradual activation of a procedure for managing the bodies of victims on the various Spanish islands (there is little information on the management of bodies found at sea or on beaches by the Moroccan authorities).

This procedure has often been limited to recovering bodies that have arrived on beaches by chance, collecting the remains of people who have died on board boats arriving on the islands, and to burying the bodies with little regard for the names of the victims, or family tracing. In Spain, the rate of identification of people who have died in migration is higher for Moroccan nationals, also thanks to the ability of families and civil society to activate the system, but remains very low for West African populations on the Canary Islands route.

Without going into the details of how the identification system works, and how many people have been identified in recent years in the Canaries (see Counting the dead – ICRC report), the most concerning point here is the gap between the number of missing persons (according to families and civil society actors) and the number of “cases” registered by the authorities:

- The Caminando Fronteras association reports 4808 victims on the Canaries route between January and June 2024, with a significant number of boats which are missing (whose shipwreck could never be confirmed). The estimated number of victims in 2023 is 6618. The number of victims since 1999 remains difficult to estimate.

- In contrast, IOM’s Missing Migrant project, which refers only to “official” cases, often corroborated by bodies found or testimonies, speaks of 4828 victims between 2014 and 2024 (including 3534 by drowning) and 959 for the year 2023 (which testifies to an exponential increase in victims in recent years).

This huge gap suggests how little consideration is given to both the searches of family members and the counter-counting work done by activists and civil society actors. But it also tells us that families and witnesses do not turn to the authorities, whom they generally do not trust, to report a disappearance, and rarely to seek help.

If we compare the data for 2023, 5659 people are missing without being taken into account by official actors. 5659 disappearances which are a concern only for their families or loved ones, and the civil society actors who are trying to support them in their impossible search. While military border control systems (which could intercept boats in difficulty) are deployed in particular close to the Moroccan and Spanish coasts, search and rescue zones south of the Canaries (notably Cape Verde and Senegal) open up such vast expanses of ocean that any search operation for a boat not tracked by GPS is simply impossible.

It should be added that SAR competencies in the area have areas of overlap (of intervention and responsibility) and are still subject to negotiation. The evolution/extension of the Moroccan SAR zone can be interpreted as an evolution of the policies of externalization of mobility control, as happened for Libya and Tunisia in the Mediterranean.

The disappearance here is thus associated with an oceanic drift that probably have taken hundreds of lives. The past few months, bodies of missing persons have been found in a boat shipwrecked on the shores of Cape Verde, and other boats have been washing up on the beaches of Brazil and the Dominican Republic.

It had already happened in 2021, off the island of Tobago, when a fisherman discovered a boat carrying the bodies of 14 young people. It had probably happened before. But now it’s happening more and more often. These are isolated cases, but they point to a scenario that is terrifying in its scope, and to the probable fate of hundreds of people who left with unseaworthy boats from the coasts of Senegal and Mauritania.

The Canary route is becoming an immense zone, where searches are almost impossible and rescues extremely complicated. The only option today is to prevent these drifts and to structure an effective state search and rescue mechanism that would intervene near the coast lines and along the potential drift paths.

Identification, research, anticipation

For bodies found on the other side of the Atlantic (as for those found in the Canary Islands and elsewhere), forensic operations can be carried out to try to identify the victims, through fragmented cooperation between international organizations, national authorities, Interpol and civil society actors.

If the authorities are committed to determining the identity of the deceased, sometimes it is enough to locate information they were carrying with them/on them to find clues to their names, and sometimes also to reconstitute the group of people present on the boat. In many cases, the direct involvement of families and loved ones is necessary, to provide information and details of the voyage.

Between 2021 and 2023, the ICRC in Paris and the Institut national des sciences appliquées (Insa-Lyon) have developed a tool that should enable the mapping of networks of people and the changing composition of groups on the move. Called SCAN (for “Share, Compile and Analyse”), it has already been used to reconstitute the list of victims of several events on the Canaries route, thanks in particular to the help of survivors whose testimonies are becoming fundamental, and to connections with civil society actors able to receive alerts from families and loved ones. For the time being, this analysis of complex networks is a tool that works retrospectively, and should facilitate forensic work based on the recovery of the bodies of people who died during migration.

However, more work needs to be done to anticipate the risk of these deadly drifts.

On the one hand, by trying to strengthen the ability of people on the move to call for help, in line with the practices already developed in the Mediterranean by the Alarm Phone network (providing information about safety at sea, informing about the importance to have a satellite phone to be able to reach the SAR authorities…), and which need to be adapted to a much more complex geographical area.

On the other hand, by reinforcing the ability of families and loved ones informed of disasters to launch rapid alerts, and by building and reinforcing secure and protected connections between the various actors, including assets that would be able to activate effective searches in the area.

From a technical point of view, this may seem feasible, but for the time being it remains difficult to change the paradigm of migration policies, which today remains essentially focused on the security dimension and the criminalization of people on the move, and which should accept as a priority the need to intervene and deploy its resources to save lives at sea, and to work to prevent the systematic disappearance of hundreds of people in the Atlantic Ocean.

Filippo Furri