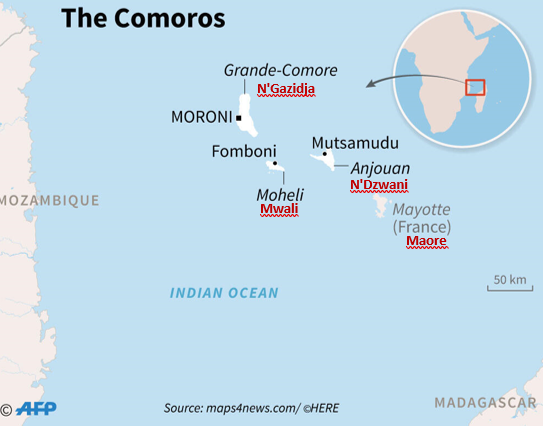

The Central Mediterranean route is considered as the world’s most deadly maritime route, but there is another route that is little known, but just as lethal: the Comoros route, which since the mid-1990s has transformed the northern Mozambique Channel into a marine graveyard. This route runs from Nosy Be, an island on the northwestern coast of Madagascar, through the three islands of the Union of the Comoros, namely N’Gazidja (Grande Comore), N’Dzwani (Anjouan) and Mwali (Mohéli), and along the East African coast to Maore (Mayotte in French), the fourth island of the Comoros archipelago, which, in violation of international law, became a territorial collectivity and then the fifth French overseas department in 2011.

The Union of the Comoros is both the point of departure for Comorians traveling or migrating to Maore and the point of convergence for nationals from the surrounding regions. Nationals of African countries (Great Lakes region, Somalia, but also West Africa) are taken by boat to N’Gazidja, from where they continue their journey via N’Dzwani, unless they are transshipped at sea in the kwasa-kwasa (the name given to the frail boats that make the journey between the Union of the Comoros and Maore), to reach their destination. Malagasy nationals, on the other hand, either ride a boat directly to Maore or transit via N’Dzwani, without being informed of this detour, where they wait several days before tackling the most dangerous part of their itinerary, i.e. the crossings being made in kwasa-kwasa instead of the more powerful motorboats used in Nosy Be.

The “Missing Migrants” project database hosted by the International Office for Migration (IMO) records 293 deaths in this region since 2014. A French Senate report published in 2012 estimates the number of people who died between 7,000 and 10,000 for the years 1995-2012, figures that are certainly underestimated and are in any case obsolete by now. The figure of 70,000 deaths would certainly be more plausible if we estimate that, for a population of around 800,000, every extended family comprising a dozen people has lost at least one member since 1995. Accidents, deaths and disappearances are both invisibilized and silenced because no international, national or civil society organization has looked into this route. Only La Cimade, in conjunction with Comorian organizations, has published a brochure and video clips to inform families about the possibilities of locating and identifying the dead and missing, and transferring them to their countries of origin.[1]

How did this seventy-kilometre channel between N’Dzwani and Maore, crisscrossed for centuries by the surrounding populations, become a deadly pathway? In 1995, anticipating the political process that would lead to the departmentalization of Maore, the French government decided to definitively sever the ancestral family and political ties linking the four “moon islands” by requiring Comorian nationals to have a visa to travel to Maore. This rarely-granted visa, also known as the “Balladur” visa after the French Prime Minister of the time, is also referred to as the “visa of death”: since they are no longer able to travel by regular sealines or airlines, Comorian nationals are left to using the kwasa kswasa, whether to attend a family or religious celebration, meet up with friends, celebrate an event, seek medical treatment or work there.

Picture: Volo-Volo Market, Moroni (NGazidja/Grande-Comore) 2021. Credit: Catherine Benoit.

Until 2002 crossings went smoothly, with few shipwrecks. That year, the Minister of the Interior, Nicolas Sarkozy, developed brutal policies to arrest and deport foreigners on land and at sea, demonstrating if proof were needed that this deadly frontier is political, not geographical. The kwasa-kwasa pilots came to leave the Comoros when the weather conditions are the most unfavorable, believing that the Comorian coastguards or French border patrols are not out in force. Over the years, they have taken increasingly dangerous routes, extending the crossing time from two hours to up to twenty-four hours, based on the location and frequency of patrols off the coast of Mayotte.

The strengthening of this French and European maritime border has accelerated since 2018: (1) creation of the Groupe d’enquête et de lutte contre l’immigration clandestine (Gelic) which came into operation on 1er September 2018, (2) Operation Shikandra initiated in 2019 which has multiplied surveillance and arrest resources on land and at sea and finally (3) signature of a framework agreement between the two countries signed on July 22, 2019 which formalizes a new partnership between the French and Comorian governments in the fight against irregular immigration with, for example, the implementation of a surveillance system to prevent departures from N’Dzwani and the financing of launches for the Comorian coastguard.

Figures published by the prefecture for 2021 and 2022 show an increase in the number of kwasa-kwasa interceptions: 459 kwasa-kwasa wereintercepted out of the 862 detected in 2021 and 571 out of 772 detected in 2022. However, these figures did not give any idea of the number of arrivals or departures, which has now been done since June 2023, when the Maore Gendarmerie announced that during the high season (April-September), around five to ten kwasa-kwasa a day seek to land, i.e. between 1,210 and 2,420 a year. This does not tell us anything about the number of departures or what happens before landing in French territorial waters, but it does give an idea of the number of boats that attempt this deadly crossing every week. In February 2024, the Minister of the Interior announced that a “maritime iron curtain” would be deployed off the island. As of now, the details have yet to be worked out.

Unlike the dead in the Mediterranean, the dead in the Mozambique Channel are generally identified when the bodies are found on the shores of N’Dzwani or Maore. In N’Dzwani, bodies that are too decomposed and unrecognizable are buried on the beaches where the ocean washes them up. A stone or a tree branch indicates the place of burial to the person who found them, but otherwise there is no trace of these sites in the landscape. Because of the climate of terror fostered by the Comorian government to keep accidents from being reported, and the criminalization of rescue efforts, families remain silent but are discreetly alerted by those who discover the bodies if they recognize them. In Maore, the fate and identification of bodies differ according to whether they were discovered by local residents or by the gendarmerie, and whether, in the case of a suspicious death, it was necessary to involve the public prosecutor and then a forensic doctor, and finally whether or not the body was handled by a mortician.

An informal system of identification is in place, depending on the willingness of the police to involve Comorian associations and community leaders in the process. Photographs of the dead circulate among them and calls on local radio stations invite Comorians to identify the bodies. In accordance with the rules of Islam, burial takes place on the day the body is discovered on a beach, or the following day if it is discovered in the late afternoon. The question of transferring the body to the Comoros does not arise, as a deceased person must be buried where he or she dies. The residents’ associations that manage the cemeteries in each commune are opposed to the burial of Comorian nationals, especially those who died at sea. Comorian landowners have come to develop sizeable cemeteries to allow the burial of bodies found on their own land, but the associations now demand that a kinship link be established between the dead person and at least one family in the commune. Muslim cemeteries have no stele to mark the dead – the memory of the cemetery owner or those who carried out the burial, and the witnesses to the burial, make up for this.

The French and Comorian authorities silence any communication attempt regarding shipwrecks, deaths and disappearances, as well as their registration. In consequence, deaths are not reported, creating endless administrative and legal problems for the families, and making mourning impossible. In addition, campaigns to prevent departures and distribute life jackets by Comorian organizations are prevented by the French government. While an official census seems out of the question – although methodologically possible – the collection of testimonies and the creation of a hotline such as those developed by Alarm Phone would make it possible to list boast in distress situations, report on kwasa-kwasa interception techniques and assess the possibility of developing rescue services in the two SAR zones of the Comoros, which are under the responsibility of Madagascar and Mozambique. France, for its part, is responsible for the SAR zone south of Madagascar and La Réunion. Since 2019, the Centre régional opérationnel de secours et de sauvetage (CROSS), has been working in partnership with the Société nationale de secours en mer (SNSM) based in Maore in the island’s territorial waters. According to the CROSS annual report, 2023 saw a 26% drop in rescue operations compared with 2022, with a total of 136 rescue operations. Of these, 99 (58%) involved the kwasa-kwasa and required 89 medical assists, i.e. almost two interventions per week for kwasa-kwasa arriving in French territorial waters (in the absence of systematic observation, we don’t know what happens in international waters or along the Comorian coast, where many shipwrecks occur right from the start).

In the meantime, a collective of civil society associations and Comorian personalities has been set up in Marseille. “La Parole aux morts” aims to record shipwrecks, the dead and the missing.

Testimonies can be posted or sent to the collective’s Facebook page at the following address:

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61556731565274

Catherine Benoît

[1] Cf. Cimade 2020 Morts et disparitions dans l’archipel des Comores. Accompagner les proches de personnes mortes ou disparues en mer, Paris.