Since 2019, the Civil MRCC has been archiving distress cases in the Central Mediterranean through it’s project, SARchive. Through this project, we have been able to better document the human rights abuses that occur as a result of coordination between the EU and the so-called[1] Libyan Coast Guard (scLYCG). The EU provides signifcant material support to the scLYCG through signed agreements such as Italy’s Memorandum of Understanding on Migration with Libya, which guarantees financial and technical support to Libyan militias signed first in 2017 and renewed again in 2023. The EU has provided around 700 million euros to Libya since 2014 in an effort to curb migration alongside other agreements signed with Tunisia and Egypt.

Interception and pushbacks of people on the move by the scLYCG happen on an almost daily bases in the Central Mediterranean. These pushbacks constitute the forcible return of people on the move to Libya, where they face detention, extortion, abuse, torture, and sexual violence in what the ICC has determined ‘may constitute crimes against humanity and war crimes.’ Such pushbacks are facilitated by Frontex and aerial surveillance provided by EU state actors.

This figure shows how Frontex aeiral surveilance capacity in terms of daily operational assets on the central Mediterranean route increased over the years. The chart reflects the determinism with which the EU is funding Frontex operations.

Through open-source tools as well as documentation provided by Civil Fleet actors, the SARchive is able to better and understand, monitor and reconstruct where and when pushbacks occur.

The animation of pushbacks shows that the vast majority of pushbacks occur in the western Libyan SAR zone and extend north into the Maltese SAR. Despite being responsible for the rescue to a safe port of disembarkation, Malta is known to regularly coordinate with the scLYCG, allowing their patrol boats to enter and conduct illegal pushbacks in Maltese SAR. Pushbacks in Malta’s SAR have increased substantially in the last few years, with a boat 10 times more likely to be intercepted and forcibly returned to Libya than rescued to Malta. In 2023 and 2024, the civil fleet also began to witness an increased trend of departures from Eastern Libya to Crete, resulting in more pushbacks in that area as well, especially north of Tobruk.

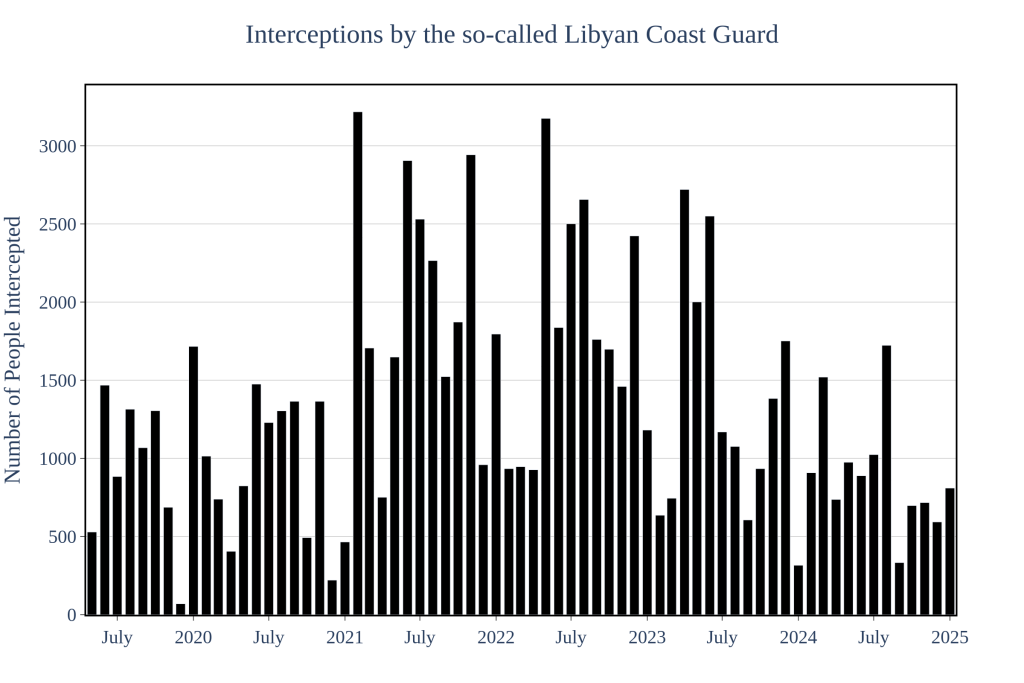

Over the last seven years, we have documented that 92,000 people have been pushed back, averaging about 1,200 people per month. The number of people pushed back per month oscillates according to weather patterns in summer and winter. Winter is especially dangerous, due to exposure to cold and harsher sea conditions. Nonetheless, the journey remains perilous even in warmer months and we have documented numerous occassions in which the scLYCG have further endangered the lives of people at sea by performing dangerous manouevres near boats in distress and even shooting in the direction of distress boats. Once back in Libya, people are detained in inhuman detention centers, where they face violence and abuse.

The scLYCG has also increased their number of operational assets with a peak in 2023 of 19. The increase of vessels available to scLYCG in 2021 and 2022 are partly a result of the Memorandum of Understanding renewed in 2022 between Italy and Libya. Italy transferred three ‘GAT’ class boats to a base in Tripoli following the finalization of the agreement and an additional two Corrubia Class vessels in June 2023.

[1] We use the addition “so-called” to certain actors to question their functionality, legitimacy and legality. For instance, the so-called Libyan Coast Guards are financed, trained, equipped, and overall supported by the European Union and single European Member States, such as Italy and Malta. They consist of different militia groups and as mentioned by the UN Fact Finding Mission on Libya in its last report (3 March 2023) “high-ranking staff of the Libyan Coast Guard,(…) colluded with traffickers and smugglers, which are reportedly connected to militia groups, in the context of the interception and deprivation of liberty of migrants.” As sea, the so-called Libyan Coast Guard use violence against people on the move and NGOs. They do not meet the basic standards required to conduct search and rescue operations and, supported by the EU and its Member States, they intercept and pull people back to Libya, exposing them to further human rights violations and potential crimes against humanity.

To read our latest analysis of the Distant-Port assignation :