On the 25th of September, there will be an early general election in Italy. Once again, a part of the election campaign is being played out on the backs of people on the move. According to the polls, Giorgia Meloni, the leader of the post-fascist party Fratelli d’Italia (‘Brothers of Italy’), could win the elections and become Prime Minister. For her, the solution is a military “naval blockade” to repel migrant boats off the coast of Libya.

Matteo Salvini, the League leader is her junior ally and is preparing to return as Minister of the Interior, a position he had already occupied from May 2018 to September 2019. He wants to reinstate the “security decrees” and try again to “close the ports” of Italy to landings.

But, beyond the propaganda, what has really happened in these four years?

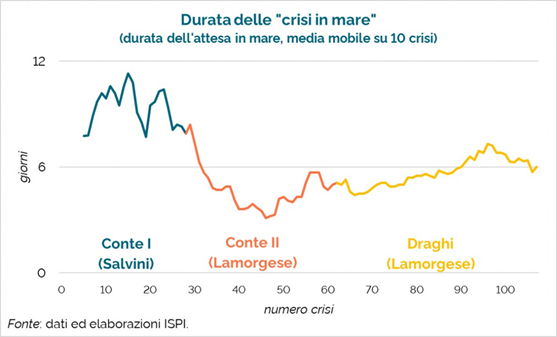

According to data collected by the reliable ISPI researcher Matteo Villa, during the Salvini period, 28 crises occurred: 12 times when rescue ships were forced to disembark in non-Italian ports, and in the rest of the cases, they were forced to wait up to 20 days before landing.

Fig. 1 CRISIS AT SEA DURATION – Moving average of stand-off length over ten cases

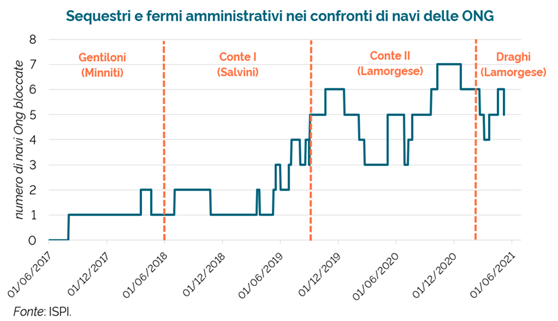

With the following two governments (Conte 2 with Mario Draghi as Prime Minister and Luciana Lamorgese as Minister of the Interior), the authorities’ attitude changed but obstacles continued to be created to civil rescue activities at sea. Since May 2020, following Port State Controls, 15 systematic administrative detentions of non-governmental ships occurred.

Fig. 2 SEIZURES AND DETENTION OF NGOs SHIPS

This practice only stopped in August 2021. In official communications with foreign authorities, new terminology has been introduced – the Italian authorities write that the ships are engaged in “systematic assistance to migrants in transit”.

But let’s now look at another specific point: in March 2020, the Covid 19 pandemic was rampant in Italy and a state of health emergency was declared. On the 7th of April, a decree by the Ministry of Transport (MIT) stated that Italian ports can no longer be considered as a “Place of Safety” for health reasons.

Quarantine ships for survivors and imposed quarantine periods for civil fleet ships themselves were established. And here too, there were significant changes in official terminology – increasingly, even rescue operations carried out by patrol boats of the Italian Coast Guard and Guardia di Finanza are not defined as “SAR events” but as “illegal immigration law enforcement operations”.

For civil rescue vessels it is always possible to disembark, often though after several days of waiting, unofficially justified by the lack of adequate reception facilities ashore. But in the official communications addressed to ships it is almost never a question of assigning a “Place of Safety”, but rather a “port of destination”, as it would be for the cargo of a merchant vessel. The state of health emergency ended on 31st March 2022, but ever since, this language continues to be used.

These are not innocent changes. On the contrary, it seems clear that the medium to long term attempt is to first of all get out of the legal framework defined by the International maritime law on SAR as defined by the Hamburg Convention of 1979, relieving European states (Italy and Malta first) of the duties and obligations that these entail.

Secondly, the aim seems to be to treat the landed persons differently – not as survivors of a SAR event seeking asylum, but rather as “illegal migrants intercepted in an irregular attempt to cross the border by sea”, resulting in more accelerated discriminatory removal procedures.

Finally, the objective is to prepare the ground for further criminalization against people on the move and against solidarity with them.

Undoubtedly, the elections in Italy on 25th September will open up new political scenarios, with impactful consequences upon the management of maritime borders in the Mediterranean.

These consequences are certainly part of a long-term strategy in border externalization, but they could also take more direct, harsh and brutal shapes. Both can and must be effectively countered through a broadening of social and political alliances and a strengthening of the common infrastructures of solidarity, at sea as well as on land.

By Beppe Caccia, Mediterranea